Picture Above - May 2018 Jo's grafting plum tree near Spruce Grove, Alberta

Newsletters and Shared Educational Material

Hello everyone. Below you will find postings of our Newsletters as well as educational materials that other fruit members want to share with the group. The shared information should be about your personal experiences in regards to growing fruits, berries, and nuts in our Canadian Prairie conditions. We welcome your trials, successes and learned lessons in these areas. Pictures are encouraged. We would like to share what works, what we are experimenting on and what failed. This page will be updated on a more regular basis as new material is shared.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 1-20 added Jan. 29, 2020

Dehorning By Thean Pheh

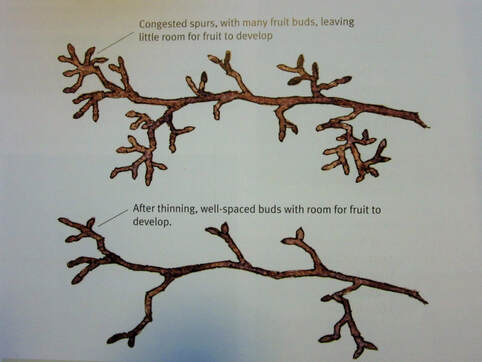

Dehorning? No, I have not lose my marbles yet. This dehorning has nothing to do with animals. Yes, it has to do with apples and pears particularly those spur bearing types. In spring a mixed bud breaks and sends forth a few leaves before terminating with a cluster of flowers. These leaves are called spur leaves. At the axil of each spur leaf is a bud. As the little apple is growing; usually around the end of May in the Edmonton area; one of these will develop and grow, producing a couple of leaves before terminating into either a vegetative or mixed bud. This results in the formation of a spur to keep the fruiting point alive for many years. However in many spur varieties more than one bud develop in some years. Hence instead of a single bud spur we now a multiple bud spur. One may give rise to two, and two to three or four, and so on. This phenomenon gives rise to what is called a complicated spur. For lack of better terminology let us name these as secondary spurs.

Normally there are anywhere from 3 to 7 flowers to a mixed bud. Hence, if there are 4 secondary spurs in a complicated spur there will be 12 to 28 flowers in that complicated spur. No matter how many secondary spurs there are on a complicated spur there should only be an apple on each complicated spur. With many more fruits to thin out fruit thinning on complicated spurs is very laborious and time consuming. Commercial growers used to prune complicated spur to a single bud. This pruning is called dehorning. Dehorning will reduce labor required for fruit thinning. Fruits also get better exposure to the sun thereby enabling them to develop deeper skin color.

Although dehorning requires less labor than fruit thinning it is nonetheless also time consuming and labor intensive. With higher labor cost and shortages it is no longer economically viable for commercial producers to dehorn. Complicated spurs may also have gone down the path of the dodo in modern high density orchards where laterals are treated as replaceable fruiting scaffolds. But for us home gardeners, where standard or semi-standard trees are still the norm and tree shapes are important part of the landscape, complicated spurs are here to stay. Since time and cost are not determining factors we must weigh our options between dehorning and timely heavy flower and fruit thinning.

Dehorning is best done in spring as part of annual pruning. Let’s take an example of a complicated spur with four secondary spurs. I try to keep the shortest and closest spur/bud to the point of origin. Instead of sharing nutrients with three other buds, all the nutrients are now channelled to the reminding one. Hence dehorning increases the vigor of the retained spur. This may spur development of more than a bud and cause the return of complicated spur. Hence dehorning of spur may be an annual affair.

Instead of dehorning some growers prefer to thin all apples to retain only one on each complicated spur. After pollination the developing apples depend on food reserves stored in the vicinity of the spur to grow. Since this supply is rather small, regardless of how many secondary spurs a complicated spur has it must be treated as a simple spur. This is my modus operandi. As soon as the flowers have elongated long enough for easy removal, I pick the strongest secondary spur and remove all flowers on the rest in that complicated spurs. With this the tree does not have to expend unnecessary energy to develop all the flowers. Energy thus saved goes directly to initiate and develop mixed buds for next year. My next step is to remove all except three flowers on the selected secondary spur. As soon as the retained flowers have bloom I start to thin out the apples, either end of May or first week of June in the Edmonton area. With this modus operandi I get bigger fruits and eliminate biennial fruiting or the well-known heavy and light fruiting cycle. There is a downside to this practice. Apples in complicated spurs are surrounded by too many leaves. This results in less colorful fruits.

Normally there are anywhere from 3 to 7 flowers to a mixed bud. Hence, if there are 4 secondary spurs in a complicated spur there will be 12 to 28 flowers in that complicated spur. No matter how many secondary spurs there are on a complicated spur there should only be an apple on each complicated spur. With many more fruits to thin out fruit thinning on complicated spurs is very laborious and time consuming. Commercial growers used to prune complicated spur to a single bud. This pruning is called dehorning. Dehorning will reduce labor required for fruit thinning. Fruits also get better exposure to the sun thereby enabling them to develop deeper skin color.

Although dehorning requires less labor than fruit thinning it is nonetheless also time consuming and labor intensive. With higher labor cost and shortages it is no longer economically viable for commercial producers to dehorn. Complicated spurs may also have gone down the path of the dodo in modern high density orchards where laterals are treated as replaceable fruiting scaffolds. But for us home gardeners, where standard or semi-standard trees are still the norm and tree shapes are important part of the landscape, complicated spurs are here to stay. Since time and cost are not determining factors we must weigh our options between dehorning and timely heavy flower and fruit thinning.

Dehorning is best done in spring as part of annual pruning. Let’s take an example of a complicated spur with four secondary spurs. I try to keep the shortest and closest spur/bud to the point of origin. Instead of sharing nutrients with three other buds, all the nutrients are now channelled to the reminding one. Hence dehorning increases the vigor of the retained spur. This may spur development of more than a bud and cause the return of complicated spur. Hence dehorning of spur may be an annual affair.

Instead of dehorning some growers prefer to thin all apples to retain only one on each complicated spur. After pollination the developing apples depend on food reserves stored in the vicinity of the spur to grow. Since this supply is rather small, regardless of how many secondary spurs a complicated spur has it must be treated as a simple spur. This is my modus operandi. As soon as the flowers have elongated long enough for easy removal, I pick the strongest secondary spur and remove all flowers on the rest in that complicated spurs. With this the tree does not have to expend unnecessary energy to develop all the flowers. Energy thus saved goes directly to initiate and develop mixed buds for next year. My next step is to remove all except three flowers on the selected secondary spur. As soon as the retained flowers have bloom I start to thin out the apples, either end of May or first week of June in the Edmonton area. With this modus operandi I get bigger fruits and eliminate biennial fruiting or the well-known heavy and light fruiting cycle. There is a downside to this practice. Apples in complicated spurs are surrounded by too many leaves. This results in less colorful fruits.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 5-19 added Nov. 12, 2019

Bernie and his pal Justin have just made 4 new short YouTube videos. All are short 3 or 4 minutes each on topics of interest to cold weather fruit growers. Just click on the link below to see these recent videos and, and also check out some of his other videos on grafting (on the same Veritas 555 777 channel).

Amazing Scionwood Storage Method. You can also read the article on this topic below ( Oct. 23, 2019)

https://youtu.be/KRSIj63iNhM

Overwintering Fig Trees in Canada

https://youtu.be/l6nzG6RicoI

Siberian Peach Tree Method - Grow Peaches in minus 40C

https://youtu.be/gvDu1EviOnU

Tree Tenting Method Add +10 to +15C in the winter

https://youtu.be/m9qWjLL6bXg

Gabe has provided this link below, to all those of you that just love more information on Fruit Growing.

https://www.pdfdrive.com/temperate-zone-pomology-physiology-and-culture-e189191108.html

...lots of other great nonfiction books available for free download as well.

Amazing Scionwood Storage Method. You can also read the article on this topic below ( Oct. 23, 2019)

https://youtu.be/KRSIj63iNhM

Overwintering Fig Trees in Canada

https://youtu.be/l6nzG6RicoI

Siberian Peach Tree Method - Grow Peaches in minus 40C

https://youtu.be/gvDu1EviOnU

Tree Tenting Method Add +10 to +15C in the winter

https://youtu.be/m9qWjLL6bXg

Gabe has provided this link below, to all those of you that just love more information on Fruit Growing.

https://www.pdfdrive.com/temperate-zone-pomology-physiology-and-culture-e189191108.html

...lots of other great nonfiction books available for free download as well.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 4-19 added Oct. 23, 2019

New Excellent Way To Store Fruit Tree Scions! By Bernie Nikolai

This has worked really well for me in the last two years testing. No matter how cold a test winter we get, the scions are in good shape for grafting in the spring. This method is ESPECIALLY good for storing scions of marginal varieties that can easily be damaged in our challenging winters due to cold temperatures.

Basically, you bury a 5 gallon plastic Home Depot pail or similar to near the rim in your garden in the shade on the north side of a fence or building. So the bottom of the pail is about 15 inches below the surface of the ground.

You cut the scions really early, not in March, but in NOVEMBER no later than the first day after the minimum temperature at night hits -15C (roughly mid November on average, but it can be earlier or later). You store them in zip lock bags with a tiny piece of damp paper towel, very similar to what you would do in April in your fridge with cut scions.

You place the scions into the bucket, snap on the plastic lid (important so spring melted snow won't melt into the bucket), and cover with a big bag of raked leaves. When it snows cover the bag of leaves with snow as well. You can check/add to/remove the scions at any time in the winter by removing the bag of leaves and taking off the lid of the bucket.

No matter how cold it gets in winter, the minimum temperature I have ever recorded is -5C all winter inside the bucket. The temperature is amazingly consistent, and only varies perhaps a half degree C in a month. Tests at Washington State University show the perfect temperature to store scions is slightly below freezing, around -1C to -5C. A freezer, even a fridge freezer, is often too cold, but this ground bucket storage method is perfect in terms of temperature! A fridge is way too warm at +5C for long term storage longer than a month or so, especially with cherries and plums.

This is the only real way to store sweet cherry and tender plum scions, as they are usually damaged by cold if you cut the scions in late March, the normal time. But you can store any variety of apple, pear, plum, cherry, etc. with this method. If a test winter kills your tree/grafts, you still have lots of good viable scions to regraft in spring from your bucket! Once the temperature in the bucket reaches +4C about mid April I move the scion bags to my fridge, and they are all grafted within about 2 weeks after that.

This method has been used for decades with excellent results in a similar climate in Russia, and I can vouch for the fact any scions are in excellent shape come grafting time in late April, May.

First photo is my buried bucket with the plastic lid snapped on, plus another identical bucket beside it to show the size. Second and third photos are looking into the bucket showing a max/min thermometer inside.

Basically, you bury a 5 gallon plastic Home Depot pail or similar to near the rim in your garden in the shade on the north side of a fence or building. So the bottom of the pail is about 15 inches below the surface of the ground.

You cut the scions really early, not in March, but in NOVEMBER no later than the first day after the minimum temperature at night hits -15C (roughly mid November on average, but it can be earlier or later). You store them in zip lock bags with a tiny piece of damp paper towel, very similar to what you would do in April in your fridge with cut scions.

You place the scions into the bucket, snap on the plastic lid (important so spring melted snow won't melt into the bucket), and cover with a big bag of raked leaves. When it snows cover the bag of leaves with snow as well. You can check/add to/remove the scions at any time in the winter by removing the bag of leaves and taking off the lid of the bucket.

No matter how cold it gets in winter, the minimum temperature I have ever recorded is -5C all winter inside the bucket. The temperature is amazingly consistent, and only varies perhaps a half degree C in a month. Tests at Washington State University show the perfect temperature to store scions is slightly below freezing, around -1C to -5C. A freezer, even a fridge freezer, is often too cold, but this ground bucket storage method is perfect in terms of temperature! A fridge is way too warm at +5C for long term storage longer than a month or so, especially with cherries and plums.

This is the only real way to store sweet cherry and tender plum scions, as they are usually damaged by cold if you cut the scions in late March, the normal time. But you can store any variety of apple, pear, plum, cherry, etc. with this method. If a test winter kills your tree/grafts, you still have lots of good viable scions to regraft in spring from your bucket! Once the temperature in the bucket reaches +4C about mid April I move the scion bags to my fridge, and they are all grafted within about 2 weeks after that.

This method has been used for decades with excellent results in a similar climate in Russia, and I can vouch for the fact any scions are in excellent shape come grafting time in late April, May.

First photo is my buried bucket with the plastic lid snapped on, plus another identical bucket beside it to show the size. Second and third photos are looking into the bucket showing a max/min thermometer inside.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 3-19 added July 5, 2019

I Do It My Way By Thean Pheh and Gabe Botar

(Collecting scionwood in February or October, storing & chip budding in July)

Thean : Most of us harvest our scionwood in March or April and then keep them in the refrigerators crisper until it’s time to graft in May to June. Based on plant physiology, I think this is a bad practice. Most plants would have already got their cold chill requirement by March. That means they could have moved because there are always days in March and April when the ambient temperature is well above the freezing point. Water that the trees had downloaded into the intercellular spaces in preparation for winter could have moved back into the cells. Refreezing of water within cells is bad or fatal for plants. Hence there is the possibility of us harvesting badly damaged scionwood. There were occasions when scionwood I harvested in February were without any damage, the sapwood were perfectly alive and white. Scionwood harvested from the same donor trees in April were either dead or the sapwood were dark brown ie dead; only the buds and cambium were alive. Success from grafting with such scionwood can be extremely poor. The temperature in most crisper is around +2oC to +4oC. Even when there is no damage, scionwood kept at this constant temperature will start to move. Hence many of us are left with dehydrated scionwood or scionwood with emerging buds when it’s time for us to graft.

To circumvent this problem I harvest my scionwood while the woods are still fully frozen, normally in Mid-February in metropolis Edmonton, well before there is a day where the temperature is above freezing. The harvested scionwood is immediately wrapped with wet paper towels and placed in a plastic freezer bag and thrown into the freezer. (Remember to label if there are more than one cultivar and try to squeeze out as much air as possible from the bag before sealing.) Not all plastic are created equal. Only freezer bag will do. Materials stored in regular plastic will suffer from freezer burns. To be sure sometimes I double freezer bagged. The scionwood is never allowed to thaw out from the trees to the freezer. One day before grafting I remove the scionwwod from the freezer and place the bag in the refrigerator to thaw out gradually.

Gabe: I would mention that I have always tried to collect scionwood in February, mainly for the reasons you have listed. Did get positive feedback on the quality of my scionwood ! The other thing I now do (since our fridge is now a self-defrosting one) is keeping the scionwood in its plastic bag inside a bubble-wrap envelope in the crisper for the few weeks until I graft, after mid-May. Not using the bubble-wrap used to result in damaged scions because of the alternating temperatures inside the self-defrosting fridge. Back at F64, I always kept the scionwood in an old-fashioned antique fridge that kept temperatures steady, and could keep scions in good shape all the way into July. (In fact, I did graft some apples in July long ago, and there was enough time for the new growth to harden off before winter.)

Thean: Yes, it can be troublesome walking through deep snow in freezing temperature to get to the donor plants. But, it’s good exercise for burning off the extra weight gained from eating too much over the end of the year and New Year festivities. This method may not be practical for most of us especially if we have to depend on getting our materials from the annual scionwood exchange in DBG or if scionwood had to be shipped in from another area.

Another method I used to practice but have abandoned for more than two decades is to harvest the scionwood in fall after all the leaves had dropped off, around October. The fence on the south side of my yard is solid 8x4 feet plywood to about 5 feet high. About three feet of soil at the north side never

get the spring sun. I buried the harvested scionwood 6 to 8 inches before covering them to about 4 inches with dried leaves collected during fall cleanup. When I was shovelling snow I threw the snow over the mulch. That will be last place in my yard to be snow free in spring. After the soil had thawed out and dry enough, normally early May, before I dug and recovered the scionwood. The wood was then stored in plastic bag in the crisper until required. The reasons I dropped this practice was too much time and labor were required. Also, very often buds on the wood had sprouted by the time I recovered them. Thirdly there were years when the soil was already frozen by October.

Gabe: For some reason, I never even tried fall scion collection, except when I was experimenting with bench-grafted interstem callusing...but that is another story again...

Thean: Commercial nursery operators produce millions of grafted trees each year. Interestingly none of them graft; every plant was budded. Why then are we not following the footsteps of the professionals? Since budding is not only easier and faster but success is also higher I do most of my propagation by budding. Alberta Agriculture recommends doing it in August to early September. I prefer to do it starting from the third week of July. I’m still in the old school and expect the first killing frost within the first week of September. (Maybe with global warming frost will come later!) Since my rule of thumb is to stop budding three weeks before the expected first frost I stop budding by mid-August. There are many methods of budding practiced around the world. The three I used are “T”, chip and a method that I came up with by combining the chip and patch methods. The disadvantage with budding in summer is the budwood is actively growing and extra precautions must be taken to prevent dehydration. Budwood is also best used within a week from harvesting.

Gabe: One disadvantage vis-a-vis grafting is the one-year delay to first flower. For hobbyists, the advantages of grafting are more obvious than for commercial orchards.

Footnote: Wood used for grafting is called scionwood while that used for budding is called budwood.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 2-19 added May 24, 2019

Gummosis, anyone ? By Gabe Botar added May 24, 2019

If you have one or more stone fruits (apricot, cherry, plum etc.) chances are that you have seen brownish-coloured resinous sap oozing from the bark of at least some of your trees. That glob of sticky sap is referred to as "gummosis" and it usually means that you need to take action if you want your tree to thrive.

The first (and usually obvious) explanation for gummosis is mechanical wounding of the bark. (Yes, woodpeckers and insects may be among the culprits.) In and of itself this may be only a minor problem, but the glob of sap will attract microbes and some of those will probably be pathogenic. Also, if you are grafting and experience gummosis at the grafting site, your graft is probably at risk for failure. (Working quickly and precisely usually alleviates this risk.)Whether the gummosis involves only mechanical injury or pathogens as well, you will need to correct the problem.

Another frequent culprit is "sunscald", sometimes called "southwest injury". During the day in late winter, solar radiation will heat up the dark-coloured bark enough to let liquid water hydrate stem tissues ; sap will start flowing upwards through the xylem. However, at that time of year overnight temperatures usually drop below the freezing point of the sap, even if that is less than zero Celsius because of the dissolved solutes in the sap. When hydrated cells freeze, their water turns to ice crystals. Now we know that ice is less dense than liquid water (that is why ice cubes float), so the crystals now occupy a larger volume than did the liquid water earlier. Result : the cell membrane breaks and the cell contents ooze into the spaces between the relatively resilient cell walls (which can also become deformed). Sap droplets appear on the surface of the bark.

Have you ever heard of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae van Hall ? (I'll call it PS here for the sake of brevity.) Pseudomonas is a genus of almost 200 types of bacteria that live in a wide variety of habitats : they can cause hospital infections, food spoilage, sick mushroom farms etc. The "syringae"in the name of the bacterium in question gives away its significance, in that it was first isolated in lilacs. PS will infect a wide range of plant species, including the stone fruits in the genus Prunus. Now PS produces ice-nucleating proteins, which cause sap to freeze at higher temperatures than would normally be the case : healthy sap usually will not freeze at -2C because of its solutes, but PS will promote some cell freezing at that temperature. See how PS can make gummosis even more likely ?

As if a mechanical trauma or primary infection by PS were not enough, various species of pathogenic fungi often enter the stem tissues to cause secondary infections. In warmer climates where sunscald is not much of a problem, fungal gummosis is ! The "cankers" (areas of usually sunken dead tissue on the bark) will spread if not eradicated, thus ultimately killing the tree if the main trunk is compromised.

What to do ? Well, the first step is to remove the globs since they may be teeming with pathogenic inocula. A paper towel soaked with 50-70% alcohol will do.

Next, if there are cankers, they will need to be "shaved" down to healthy wood, provided the cankers are not too deep (in which case the affected branch needs to be pruned off carefully, making sure not to spread the inoculum.) The shaved area is then swabbed with alcohol or given a short sterilizing blast with a propane torch (not both !) and finally it is spray-painted or brushed with anti-rust paint.

Finally, the whole trunk should be kept painted with white latex paint. This procedure is useful for two reasons. The first is that white reflects sunlight, so the bark will not heat up as easily in late winter -- ice crystals are less likely to form, so cell damage is minimized. Secondly, any gummosis will be more easily spotted against a white background. Some people also add fungicides to the latex paint (for obvious reasons) and maybe even a bitter substance such as denatonium benzoate (Bitrex) to deter gnawing mammals. If you have ever used Skoot as a deterrent, you may have noticed that its bitter prime ingredient Thiram is also a potent fungicide !

In summary, gummosis can be a serious problem in Prunus trees. Where possible, prune out affected branches. (Bag, burn or bury the prunings -- do not leave them lying around !) Otherwise, clean and sterilize cankers to destroy as much inoculum as possible. Paint trees with white latex to prevent sunscald, and repeat as needed.

The first (and usually obvious) explanation for gummosis is mechanical wounding of the bark. (Yes, woodpeckers and insects may be among the culprits.) In and of itself this may be only a minor problem, but the glob of sap will attract microbes and some of those will probably be pathogenic. Also, if you are grafting and experience gummosis at the grafting site, your graft is probably at risk for failure. (Working quickly and precisely usually alleviates this risk.)Whether the gummosis involves only mechanical injury or pathogens as well, you will need to correct the problem.

Another frequent culprit is "sunscald", sometimes called "southwest injury". During the day in late winter, solar radiation will heat up the dark-coloured bark enough to let liquid water hydrate stem tissues ; sap will start flowing upwards through the xylem. However, at that time of year overnight temperatures usually drop below the freezing point of the sap, even if that is less than zero Celsius because of the dissolved solutes in the sap. When hydrated cells freeze, their water turns to ice crystals. Now we know that ice is less dense than liquid water (that is why ice cubes float), so the crystals now occupy a larger volume than did the liquid water earlier. Result : the cell membrane breaks and the cell contents ooze into the spaces between the relatively resilient cell walls (which can also become deformed). Sap droplets appear on the surface of the bark.

Have you ever heard of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae van Hall ? (I'll call it PS here for the sake of brevity.) Pseudomonas is a genus of almost 200 types of bacteria that live in a wide variety of habitats : they can cause hospital infections, food spoilage, sick mushroom farms etc. The "syringae"in the name of the bacterium in question gives away its significance, in that it was first isolated in lilacs. PS will infect a wide range of plant species, including the stone fruits in the genus Prunus. Now PS produces ice-nucleating proteins, which cause sap to freeze at higher temperatures than would normally be the case : healthy sap usually will not freeze at -2C because of its solutes, but PS will promote some cell freezing at that temperature. See how PS can make gummosis even more likely ?

As if a mechanical trauma or primary infection by PS were not enough, various species of pathogenic fungi often enter the stem tissues to cause secondary infections. In warmer climates where sunscald is not much of a problem, fungal gummosis is ! The "cankers" (areas of usually sunken dead tissue on the bark) will spread if not eradicated, thus ultimately killing the tree if the main trunk is compromised.

What to do ? Well, the first step is to remove the globs since they may be teeming with pathogenic inocula. A paper towel soaked with 50-70% alcohol will do.

Next, if there are cankers, they will need to be "shaved" down to healthy wood, provided the cankers are not too deep (in which case the affected branch needs to be pruned off carefully, making sure not to spread the inoculum.) The shaved area is then swabbed with alcohol or given a short sterilizing blast with a propane torch (not both !) and finally it is spray-painted or brushed with anti-rust paint.

Finally, the whole trunk should be kept painted with white latex paint. This procedure is useful for two reasons. The first is that white reflects sunlight, so the bark will not heat up as easily in late winter -- ice crystals are less likely to form, so cell damage is minimized. Secondly, any gummosis will be more easily spotted against a white background. Some people also add fungicides to the latex paint (for obvious reasons) and maybe even a bitter substance such as denatonium benzoate (Bitrex) to deter gnawing mammals. If you have ever used Skoot as a deterrent, you may have noticed that its bitter prime ingredient Thiram is also a potent fungicide !

In summary, gummosis can be a serious problem in Prunus trees. Where possible, prune out affected branches. (Bag, burn or bury the prunings -- do not leave them lying around !) Otherwise, clean and sterilize cankers to destroy as much inoculum as possible. Paint trees with white latex to prevent sunscald, and repeat as needed.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 1-19 added Feb. 7, 2019

Summary of info gathered in Grafting Laboratory, Pl.Sc. 335.

Grafting Fruit Compatibility-Hints By Gabe Botar added Feb. 7, 2019

1. Know your plant material ! This will guide you in choosing compatible stocks and scions, and give you greater control over the final size, shape and makeup of your grafted plant .

2. Safety above all !!! Use appropriate tools. Your grafting/budding knife must be razor-sharp, rigid and unbreakable. When tying/sealing the graft area, be aware that in order to prevent girdling you may eventually need to cut the cloth tape, raffia, etc. used to hold the stock and scion together. (Softer materials such as rubber budding strips, parafilm, and masking tape will usually degrade and fall off on their own, without needing to be cut. Vinyl tape and rubber/silicone tape will probably need monitoring/cutting to prevent girdling.)

3. Evergreen tropical plants and greenhouse ornamentals can usually be grafted in any season, but spring is usually best since day length is increasing then. Monocots cannot be grafted.

4. In the Edmonton area, observe the following Rules of Thumb for fruit trees (apples, pears, plums, cherries) :

a. Collect dormant scionwood/budsticks in late February/early March ; store with a moist (not wet !) paper towel in a sealed plastic bag in the refrigerator, at 2-4C. ((Scions may last for months if kept this way at 2C…and for a week or so if kept at 10C.)

b. Graft or bud after May 1. The best time is about mid-May. At this point the sap is rising in the stock but the scions should still be dormant. If you can keep a scion dormant, it may be grafted successfully onto a suitable rootstock as late as July, and still make growth and harden off in time for the coming winter. All the grafts will work this way, as will chip & Jones buds.

c. The first week in August is usually the “window” for doing T-buds, because the stock bark is “slipping” then. Whereas the scionwood/ budsticks used around May 1 and later have no foliage, T-buds will have leaves at the nodes. (Remove the leaf blades but keep the petioles, which are good little handles ; after the budding procedure, the petioles should fall off after 10 days or so.) On the budstick, avoid basal and terminal buds, choosing the plump and mature medial buds of the current season’s growth. Jones and chip buds do not need to have the stock bark "slipping" and have a wider latitude for budding time.

5. Be clear about the difference between TOPWORKING and FRAMEWORKING, and the advantages of each.

6. Some Grafting Compatibility Hints Below:

a. Graft Apples : A species is usually graft-compatible on its own seedlings ; thus, an apple will usually graft successfully onto an apple, etc. In our climate, just about any Malus scion will graft onto the same or another Malus cultivar or species. Crabapples and large-fruited apples can be grafted onto each other, but be aware of what can happen when stocks and scions with very different growth rates and growth habits are combined.

b. Graft plums and cherry-plum hybrids onto most plums, sandcherry, or nanking cherry.

c. Graft hardy apricots onto sandcherry, but not onto nanking cherry or plum (some salicinas excepted), unless you want to hold the scion for only a couple of seasons or less before final grafting onto a sandcherry. Apricots on sandcherry need to be staked. If you use sandcherry as an interstem, apricots will usually do well on plums and nanking cherries.

d. Graft pears onto saskatoons and cotoneasters and some hawthorns (especially Japanese) and mountain ash. Note the need to keep some of the original foliage below the graft on saskatoons and cotoneasters. Compatible mountain ash rootstocks do not have this requirement and usually do not need staking. If using seedlings for pear rootstocks, use seeds from hybrid hardy pears rather than seeds from pure Ussurian pear lines.

e. Graft saskatoons onto cotoneaster (usually successful) or compatible mountain ash. If the compatibility with the mountain ash is unknown, try a cotoneaster interstem.

f. Graft sour cherry onto mongolian cherry or pincherry (or hardy sweet cherry in relatively warm microclimates). Seedlings of the sour cherry 'Evans' are usually compatible stocks for sweet and sour

cherries here but often short-lived. Alternatively, sweet and sour cherries can usually be grafted onto Amur cherry or Amur cherry interstems on mayday. The hardiest sweet cherries in our area usually graft well onto 'Evans' sour cherry. The true (sweet and sour) cherries are usually not compatible on sandcherry or nanking cherry, which are more closely related to plums.

g. Graft chokecherry onto amur cherry, or mayday (usually, but not always; consider using an Amur cherry interstem on maydays). (Chokecherries are not compatible with the true cherries in f. above).

h. Graft red and white currants and gooseberries onto Ribes aureum or its close relatives (usually successful) ; the resulting plants are taller, more productive, and easier to harvest).

i. Common (French) lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) often sucker badly. They can be grafted successfully onto non-suckering late lilacs (Syringa villosa) only if an interstem of dwarf Korean lilac (Syringa meyeri) is used

2. Safety above all !!! Use appropriate tools. Your grafting/budding knife must be razor-sharp, rigid and unbreakable. When tying/sealing the graft area, be aware that in order to prevent girdling you may eventually need to cut the cloth tape, raffia, etc. used to hold the stock and scion together. (Softer materials such as rubber budding strips, parafilm, and masking tape will usually degrade and fall off on their own, without needing to be cut. Vinyl tape and rubber/silicone tape will probably need monitoring/cutting to prevent girdling.)

3. Evergreen tropical plants and greenhouse ornamentals can usually be grafted in any season, but spring is usually best since day length is increasing then. Monocots cannot be grafted.

4. In the Edmonton area, observe the following Rules of Thumb for fruit trees (apples, pears, plums, cherries) :

a. Collect dormant scionwood/budsticks in late February/early March ; store with a moist (not wet !) paper towel in a sealed plastic bag in the refrigerator, at 2-4C. ((Scions may last for months if kept this way at 2C…and for a week or so if kept at 10C.)

b. Graft or bud after May 1. The best time is about mid-May. At this point the sap is rising in the stock but the scions should still be dormant. If you can keep a scion dormant, it may be grafted successfully onto a suitable rootstock as late as July, and still make growth and harden off in time for the coming winter. All the grafts will work this way, as will chip & Jones buds.

c. The first week in August is usually the “window” for doing T-buds, because the stock bark is “slipping” then. Whereas the scionwood/ budsticks used around May 1 and later have no foliage, T-buds will have leaves at the nodes. (Remove the leaf blades but keep the petioles, which are good little handles ; after the budding procedure, the petioles should fall off after 10 days or so.) On the budstick, avoid basal and terminal buds, choosing the plump and mature medial buds of the current season’s growth. Jones and chip buds do not need to have the stock bark "slipping" and have a wider latitude for budding time.

5. Be clear about the difference between TOPWORKING and FRAMEWORKING, and the advantages of each.

6. Some Grafting Compatibility Hints Below:

a. Graft Apples : A species is usually graft-compatible on its own seedlings ; thus, an apple will usually graft successfully onto an apple, etc. In our climate, just about any Malus scion will graft onto the same or another Malus cultivar or species. Crabapples and large-fruited apples can be grafted onto each other, but be aware of what can happen when stocks and scions with very different growth rates and growth habits are combined.

b. Graft plums and cherry-plum hybrids onto most plums, sandcherry, or nanking cherry.

c. Graft hardy apricots onto sandcherry, but not onto nanking cherry or plum (some salicinas excepted), unless you want to hold the scion for only a couple of seasons or less before final grafting onto a sandcherry. Apricots on sandcherry need to be staked. If you use sandcherry as an interstem, apricots will usually do well on plums and nanking cherries.

d. Graft pears onto saskatoons and cotoneasters and some hawthorns (especially Japanese) and mountain ash. Note the need to keep some of the original foliage below the graft on saskatoons and cotoneasters. Compatible mountain ash rootstocks do not have this requirement and usually do not need staking. If using seedlings for pear rootstocks, use seeds from hybrid hardy pears rather than seeds from pure Ussurian pear lines.

e. Graft saskatoons onto cotoneaster (usually successful) or compatible mountain ash. If the compatibility with the mountain ash is unknown, try a cotoneaster interstem.

f. Graft sour cherry onto mongolian cherry or pincherry (or hardy sweet cherry in relatively warm microclimates). Seedlings of the sour cherry 'Evans' are usually compatible stocks for sweet and sour

cherries here but often short-lived. Alternatively, sweet and sour cherries can usually be grafted onto Amur cherry or Amur cherry interstems on mayday. The hardiest sweet cherries in our area usually graft well onto 'Evans' sour cherry. The true (sweet and sour) cherries are usually not compatible on sandcherry or nanking cherry, which are more closely related to plums.

g. Graft chokecherry onto amur cherry, or mayday (usually, but not always; consider using an Amur cherry interstem on maydays). (Chokecherries are not compatible with the true cherries in f. above).

h. Graft red and white currants and gooseberries onto Ribes aureum or its close relatives (usually successful) ; the resulting plants are taller, more productive, and easier to harvest).

i. Common (French) lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) often sucker badly. They can be grafted successfully onto non-suckering late lilacs (Syringa villosa) only if an interstem of dwarf Korean lilac (Syringa meyeri) is used

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 2-18 added Sept. 26, 2018

My Blueberry Story By Thean Pheh added Sept. 26, 2018

Blueberries are native to many temperate countries around the world. Several species are native to North America. Among those native to Canada are the highbush, low sweet, ground hurt and velvet leaf. Only the velvet leaf, Vaccinium myrtilloides is native to Alberta. Lesser known is the black huckleberry, Vaccinium membranaceum, a very close relative that can be found in some parts of the Rocky Mountains.

Long before nutritionists touted blueberry as superfood it was highly valued by First Nation people and our forefathers. Many family outings used to be planned around the period when the native blueberries were ripening. Areas that produced heavily or high qualities berries were family’s top secrets.

With better transportation and storage facilities more and more berries are available in stores that resulted in less and less family outings nowadays. In the past demands for blueberry plants were very low to non-existence. However frequent airing and published articles on the health benefits of blueberry turned the table. More and more gardeners want to grow their own and this encourages every garden centres to carry some seedlings in spring.

Blueberries like all species in the Vacccinium Genus are very fussy and require very acidic soils to grow well. Most literature noted pH ranges from 4.5 to 6 as ideal. Although pines, Pinus spp. will tolerate neutral soil they grow best in slightly acidic soil. Over time they alter the soil reaction and lower the pH slightly. That’s why rookie blueberry foragers are told to look for pine forest to begin their hunt.

I envy some of our members who are on isolated pockets of acidic soil. When I started in the 80s, like every other gardener, I was told to amend my bed with liberal amount of peat moss before planting. I did that. A season of optimism soon turned sour when I inherited nothing but frustration and anguish. The pH of the black Chernozemic soil in Edmonton and immediate surrounding area is around 7.2 or higher. With high OM and clay it is very difficult to amend and maintain the adjusted pH for long: the upward moisture movement soon increases the pH within a couple of years. A couple of specialists suggested application of aluminium sulphate but I was hesitant because excess of aluminium leads to toxicity that can make growing any plants very, very difficult. Sulphur was also recommended but sulphur takes too many years to affect soil pH changes. Almost all blueberry plants sold in Alberta are hybrids between the low sweet x highbush blueberries - V. angustifolium x V. corymbosum. Although most literature listed them as hardy to Zone 3 results are very, very inconsistent and disappointing. The plants survived but suffered from severe winterkill(1). Since the initiated floral buds are on last year’s wood winterkill meant no flowers and berries. By the early 90s I gave up growing blueberries.

I was transferred to Brooks in 2002. The end of spring sales was too good to pass and I ended buying a Northblue and a Northline blueberry plants. The brown Chernozemic soil in my yard was not only alkaline but also slightly saline. Since I was already into bonsai or penjing I decided to grow the two plants in containers. The small volume of soil in container is so much easier to adjust and maintain. The other reason is providing extra winter protection is a breeze when plants are planted in containers. In fall before the snow flies I placed the pots on its side and cover the canes with fallen leaves collected from other trees. Snow added more insulation. By resisting the temptation to uncover the plants as soon as the snow had melted in spring, I have been harvesting blueberries since then (2).

Acidic soil restricts the availability of many nutrients. Blueberries overcome that by developing a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizae, a soil dwelling fungus. As such do not wash off any soil that come with your purchased plants. If you dig from the wild, be sure to bring home some soil with your dug out plants. I mix my own potting soil using equal volume of play sand, peat moss and soil from my yard. How do I keep the pH low? I water with Ammonium sulphate in spring and fertigate with water soluble fertilizers formulated for roses or evergreens every 7 to 10 days from June to end of August. To avoid building up the salinity I use ¼ of the recommended rate. For daily watering I try not to use tap water since Edmonton’s supply is alkaline. I either use rainwater collected from the roof into barrels or I use ‘rice’ water. (I collect water used for washing rice before cooking or pasta water (without salt) and allow it to ferment for several days.) Instead of throwing away the water used for rinsing milk containers, I use it to water my blueberry or lingonberry plants (3).

I do not have honey bees in my yard and as such I do not know if honey bees are attracted to blueberry’s flowers. So far I noticed that the various bumblebees are the only native bees that work among my blueberries.

(1) I found even the local velvet leaf blueberry suffered winterkill unless it is under snow.

(2) In truth I pick very little; my grandchildren beat me to the berries every year.

(3) Milk not only helps to lower pH when it sours but also is beneficial to soil microbes.

Footnote

If you have success growing blueberries in other ways, please share your secrets. Other growers will appreciate your generosity. Last year I met a gardener who dug down to two feet and lined the bottom and sides with plastic. After punching a few holes at the bottom to allow excess water to drain out he filled it with purchased potting soil. With this method he needs not water his plants every day. For winter protection he erected a wall with chicken wire netting around his blueberry plants and filled it with leaves or straw.

There are other berries that are easily grown in Alberta. These berries not only have just as much or more antioxidants than blueberries they are also much less demanding. Saskatoon, black elderberry, black currant, Aronia and haskap are excellent examples. So if you do not want to go through the hassle of watering container grown blueberry every day, plant these alternatives instead.

Long before nutritionists touted blueberry as superfood it was highly valued by First Nation people and our forefathers. Many family outings used to be planned around the period when the native blueberries were ripening. Areas that produced heavily or high qualities berries were family’s top secrets.

With better transportation and storage facilities more and more berries are available in stores that resulted in less and less family outings nowadays. In the past demands for blueberry plants were very low to non-existence. However frequent airing and published articles on the health benefits of blueberry turned the table. More and more gardeners want to grow their own and this encourages every garden centres to carry some seedlings in spring.

Blueberries like all species in the Vacccinium Genus are very fussy and require very acidic soils to grow well. Most literature noted pH ranges from 4.5 to 6 as ideal. Although pines, Pinus spp. will tolerate neutral soil they grow best in slightly acidic soil. Over time they alter the soil reaction and lower the pH slightly. That’s why rookie blueberry foragers are told to look for pine forest to begin their hunt.

I envy some of our members who are on isolated pockets of acidic soil. When I started in the 80s, like every other gardener, I was told to amend my bed with liberal amount of peat moss before planting. I did that. A season of optimism soon turned sour when I inherited nothing but frustration and anguish. The pH of the black Chernozemic soil in Edmonton and immediate surrounding area is around 7.2 or higher. With high OM and clay it is very difficult to amend and maintain the adjusted pH for long: the upward moisture movement soon increases the pH within a couple of years. A couple of specialists suggested application of aluminium sulphate but I was hesitant because excess of aluminium leads to toxicity that can make growing any plants very, very difficult. Sulphur was also recommended but sulphur takes too many years to affect soil pH changes. Almost all blueberry plants sold in Alberta are hybrids between the low sweet x highbush blueberries - V. angustifolium x V. corymbosum. Although most literature listed them as hardy to Zone 3 results are very, very inconsistent and disappointing. The plants survived but suffered from severe winterkill(1). Since the initiated floral buds are on last year’s wood winterkill meant no flowers and berries. By the early 90s I gave up growing blueberries.

I was transferred to Brooks in 2002. The end of spring sales was too good to pass and I ended buying a Northblue and a Northline blueberry plants. The brown Chernozemic soil in my yard was not only alkaline but also slightly saline. Since I was already into bonsai or penjing I decided to grow the two plants in containers. The small volume of soil in container is so much easier to adjust and maintain. The other reason is providing extra winter protection is a breeze when plants are planted in containers. In fall before the snow flies I placed the pots on its side and cover the canes with fallen leaves collected from other trees. Snow added more insulation. By resisting the temptation to uncover the plants as soon as the snow had melted in spring, I have been harvesting blueberries since then (2).

Acidic soil restricts the availability of many nutrients. Blueberries overcome that by developing a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizae, a soil dwelling fungus. As such do not wash off any soil that come with your purchased plants. If you dig from the wild, be sure to bring home some soil with your dug out plants. I mix my own potting soil using equal volume of play sand, peat moss and soil from my yard. How do I keep the pH low? I water with Ammonium sulphate in spring and fertigate with water soluble fertilizers formulated for roses or evergreens every 7 to 10 days from June to end of August. To avoid building up the salinity I use ¼ of the recommended rate. For daily watering I try not to use tap water since Edmonton’s supply is alkaline. I either use rainwater collected from the roof into barrels or I use ‘rice’ water. (I collect water used for washing rice before cooking or pasta water (without salt) and allow it to ferment for several days.) Instead of throwing away the water used for rinsing milk containers, I use it to water my blueberry or lingonberry plants (3).

I do not have honey bees in my yard and as such I do not know if honey bees are attracted to blueberry’s flowers. So far I noticed that the various bumblebees are the only native bees that work among my blueberries.

(1) I found even the local velvet leaf blueberry suffered winterkill unless it is under snow.

(2) In truth I pick very little; my grandchildren beat me to the berries every year.

(3) Milk not only helps to lower pH when it sours but also is beneficial to soil microbes.

Footnote

If you have success growing blueberries in other ways, please share your secrets. Other growers will appreciate your generosity. Last year I met a gardener who dug down to two feet and lined the bottom and sides with plastic. After punching a few holes at the bottom to allow excess water to drain out he filled it with purchased potting soil. With this method he needs not water his plants every day. For winter protection he erected a wall with chicken wire netting around his blueberry plants and filled it with leaves or straw.

There are other berries that are easily grown in Alberta. These berries not only have just as much or more antioxidants than blueberries they are also much less demanding. Saskatoon, black elderberry, black currant, Aronia and haskap are excellent examples. So if you do not want to go through the hassle of watering container grown blueberry every day, plant these alternatives instead.

Sassed of the Past By Gabe Botar added Sept. 26, 2018

When in 1977 I started working for the organization then known as the Department of Plant Science at the University of Alberta, I quickly became enamoured of the Department's large fruit orchard.

The orchard was then located on the site now occupied by the J.G. O'Donoghue Building, which came about after the sale of U of A land to the Province of Alberta. Much of the orchard could not be moved so seedlings were budded and planted at the U of A's South Campus Crops Unit in 1984. The new small germplasm repository suffered serious setbacks from the beginning and had to be terminated in the nineties. An attempt to save at least some of the unique germplasm resulted in the new mini-orchard now (since 2015) operated by the Green and Gold Garden .

Over the years, the U of A has introduced a number of useful and profitable plant lines, especially in field crops such as wheat and canola. I became interested in the fate of the few fruit introductions effected by the U of A and so came across mention of two apple cultivars, 'George' and 'Harcourt'. I had been able to taste the Harcourt and found it to be an excellent little summer apple...but there was no trace of the 'George' anywhere. What had happened to it?

Well, apparently a Mr. Robert George had planted a McIntosh seedling around 1934 and found the fruit to be medium to large (up to 7cm across), similar to Staymared, frost-resistant and of high quality. It would store until late winter and the mother tree itself was deemed to be well-formed and fire blight-resistant. The U of A purchased the tree for $1000 and released scions for testing at various prairie sites in 1948. Unfortunately, the data collected at those sites painted a somewhat less flattering picture of the fruit: it was smallish (6cm across), large-cored, and not a particularly good keeper. The verdict: there were other more promising apple lines for the prairies. The 'George' faded into oblivion...

Now the 'Harcourt', released in 1955 and still found here and there, apparently has fruit that is very similar in size, shape and colour to the 'George' of the test sites. It is interesting to note that it was named after Prof. George Harcourt, who taught horticulture at the U of A from 1915 until 1935. This little apple is definitely not a McIntosh seedling and it is not a good keeper...but to this day there are few prairie apples that can match it for quality when it is eaten out of hand at the correct degree of ripeness.

The passing years have seen both changes and stability at the Green and Gold Garden orchard: PF-47 became 'Red Sparkle', PF-51 is now 'Norkent'...and the 'Dolgo' crabapple is still one of the best for jelly. The old (and obsolete, according to some) 'Heyer 12' is still around and also appreciated for its cold-hardiness, heavy yields most years, pinkish jelly (if one ignores the maggots in the raw fruit) and good applesauce in a maggotless year...

Stories of individual fruit lines abound and sometimes evoke nostalgia for times past. Perhaps hearing these tales will open our eyes to the ever-present danger of losing cultivars that were cherished by our forebears and may yet be cherished again by those who follow us...

The orchard was then located on the site now occupied by the J.G. O'Donoghue Building, which came about after the sale of U of A land to the Province of Alberta. Much of the orchard could not be moved so seedlings were budded and planted at the U of A's South Campus Crops Unit in 1984. The new small germplasm repository suffered serious setbacks from the beginning and had to be terminated in the nineties. An attempt to save at least some of the unique germplasm resulted in the new mini-orchard now (since 2015) operated by the Green and Gold Garden .

Over the years, the U of A has introduced a number of useful and profitable plant lines, especially in field crops such as wheat and canola. I became interested in the fate of the few fruit introductions effected by the U of A and so came across mention of two apple cultivars, 'George' and 'Harcourt'. I had been able to taste the Harcourt and found it to be an excellent little summer apple...but there was no trace of the 'George' anywhere. What had happened to it?

Well, apparently a Mr. Robert George had planted a McIntosh seedling around 1934 and found the fruit to be medium to large (up to 7cm across), similar to Staymared, frost-resistant and of high quality. It would store until late winter and the mother tree itself was deemed to be well-formed and fire blight-resistant. The U of A purchased the tree for $1000 and released scions for testing at various prairie sites in 1948. Unfortunately, the data collected at those sites painted a somewhat less flattering picture of the fruit: it was smallish (6cm across), large-cored, and not a particularly good keeper. The verdict: there were other more promising apple lines for the prairies. The 'George' faded into oblivion...

Now the 'Harcourt', released in 1955 and still found here and there, apparently has fruit that is very similar in size, shape and colour to the 'George' of the test sites. It is interesting to note that it was named after Prof. George Harcourt, who taught horticulture at the U of A from 1915 until 1935. This little apple is definitely not a McIntosh seedling and it is not a good keeper...but to this day there are few prairie apples that can match it for quality when it is eaten out of hand at the correct degree of ripeness.

The passing years have seen both changes and stability at the Green and Gold Garden orchard: PF-47 became 'Red Sparkle', PF-51 is now 'Norkent'...and the 'Dolgo' crabapple is still one of the best for jelly. The old (and obsolete, according to some) 'Heyer 12' is still around and also appreciated for its cold-hardiness, heavy yields most years, pinkish jelly (if one ignores the maggots in the raw fruit) and good applesauce in a maggotless year...

Stories of individual fruit lines abound and sometimes evoke nostalgia for times past. Perhaps hearing these tales will open our eyes to the ever-present danger of losing cultivars that were cherished by our forebears and may yet be cherished again by those who follow us...

Jo Granger's note- Check out this Green and Gold Garden webpage and Gabe Botar's contribution to fruit

https://www.greengoldgarden.com/produce-for-august-14-and-18-2018/

https://www.greengoldgarden.com/produce-for-august-14-and-18-2018/

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 1-18 added Feb. 12, 2018

Interstems By Thean Pheh added Feb. 12, 2018

In the last issue, we discussed delayed incompatibility in inter-genera grafting. To a certain extent this problem can be quite easily solved with an interstem. The process involves double grafting (some refer to this as double working) where a variety that is fully compatible with two varieties are used as the ‘Mr. In Between’. That was what Bernie was talking about when he wrote about using two apple cultivars, Winter Banana and Palmetta, grafted on apple rootstocks before grafting the pears. The concept of using a Mr. In Between is not new; it had been practiced since ‘God knows when’. At one time it was widely used in the pear industry. The quince rootstock used in the old days would not accept the Bartlett pear, one of the most popular and widely planted in the world. However it is fully compatible with Old Home pear and Old Home is fully compatible with Bartlett. So to overcome the rejection growers used Old Home as the interstem. (With better and more suitable quince and other rootstocks now available I believe this practice is no longer used.)

Besides overcoming incompatibility and delayed incompatibility, interstem is useful for other purposes. M9 is the most widely used dwarfing apple rootstock in the world. It is very precocious but unfortunately has very poor root systems that cannot provide sufficient anchorage. (They must be supported for life either with individual stakes or wires.) So, someone came up with the idea of double working - using non-dwarfing rootstocks like M106 to provide good anchorage, grafting M9 onto it and then grafting the desired cultivar onto the M9. In this way well anchored dwarfing precocious apple trees are produced. (Who says you cannot have your cake and eat it too?) Unfortunately they soon ran into problems because the results were inconsistent and most plantings did not produced the desirable dwarfing effects. That resulted in heated debates on the wisdom of using double working for this purpose. It was later found that the length of the interstem played a critical role in the dwarfing effect. There must be a minimum of 8 inches for interstock for the dwarfing effect to kick in. (With today’s practice of ultra-high density planting commercial growers prefer to stake their trees instead of double working.)

Is interstem of any use to us on the harsh prairie? Most growers in Saskatchewan and a handful in Alberta use O3 or V3 as rootstocks. However O3 is not suitable in all areas. I find its stem is hardy but the roots are not; the roots must have consistent snow cover throughout winter. V3 was tested at CDCN for five years. Results were very encouraging but there is insufficient data to say with any confidence as far as its hardiness is concerned*. Gardeners in metropolitan Edmonton will have no problem with O3 or V3. However double working still merits consideration since we are in very windy country and strong gusts are frequent. In my opinion double working is definitely worth looking into for those living in Edmonton who want well anchored precocious dwarfing apple trees. Gardeners living outside the city or in rural areas may have no choice or will get better chances with double worked trees if precocious dwarfing apple/crabapple trees are desirable.

* O3 was among one of the rootstocks used as control. They failed before the test ended. Data from five years is insufficient for such long term cultural trial.

Enthusiasts of Bonsai, Penjing or container growing may find interstem useful. Malus spp. grown in containers are prime candidates for winterkill. More often than not the tops come through winter without injury but it is the roots that are completely killed. Using open pollinated seedlings as rootstocks I experienced much anguish over the years. I found most are killed in test winters but some are capable of tolerating the extremely cold even when the containers are not buried for added protection. My most hardy is an open pollination Viking crab. It was seeded in a container and after 21 years it is still very healthy without added winter protection. McIntosh grafted on it in 1997 is still productive while those grafted onto O3 and others died in one, at most three winters. In each and every case the buds began to move but dried up soon because the roots were dead. (In some cases the rootstocks were dead to the soil line and others were dead to the union.) Unfortunately this very hardy rootstock is neither dwarfing nor precocious.

Another potential commercial application is for disease control although I do not see any application for us. Rubber tree, Heavea brazillensis, is native to the Amazon Basin in Brazil. However Brazil lost its status as a major producer of rubber after Henry Wickham successfully smuggled some seeds out of the Orinoco Basin. Trees in Brazil are susceptible to a deadly disease known as the South American Leaf Blight (SALB), Microcyclus ulei. (Malaysia together with Indonesia, where SALB is absent, produce over 80% of the world’s natural rubber.) The useful or productive part of the rubber tree is the trunk. Since rubber cannot be propagated with stem cuttings, many Malaysian growers graft selected clones onto PBIG rootstocks. Unfortunately the crown of modern high yielding clones like the RIM 600 Series are very susceptible to this deadly disease. RRIM (Rubber Research Institute of Malaysia&) found a SALB resistant selection but it is totally useless because it is an extremely poor latex producer. Hence they embarked on the biggest double working trial in the world by testing the feasibility of having compound trees with 4 inches of PBIG, 8 to 10 feet of RRIM 604 and the rest of the top is the SALB resistant selection^. (The reason for the long interstem is because in harvesting only the bottom 8 feet of the trunk is tapped for the latex.)

& RRIM is the largest research institution in the world devoted to a single crop.

^ I do not know the results or the status of this trial because I left the country a few years after the trial was initiated.

Many of us are adding new cultivars to branches of existing trees. If the trees are on their own roots we are stem building. Agriculture Canada used to recommend using Malus baccata ‘Nertchinsk’ for stem building to impart winter hardiness. Most of us plant grafted trees and are merely adding more cultivars onto existing branches. Hence in a way we are using our grafted trees as the interstems. A word of caution is warrantied; multiple cultivars trees must be pruned carefully to avoid excessive growth and vigor of one cultivar to the detriment of another because some cultivars are more vigorous or compatible than others with the interstem.

This and That

Thank you, Dr. Ken Fry for responding to the last issue. Since almost all of us have saskatoon in our yard this information is of tremendous value.

Dr. Fry wrote. “As for WEA and its impact on saskatoons, they are most damaging to the establishment of saskatoon seedlings but in some research trials I did at CDC-North, I treated saskatoons with orthene to kill the aphids on the roots of saskatoons and left other saskatoons untreated and then recorded the yield over a period of 5 years. In the treated saskatoons, by year 3 the yield was significantly higher than the untreated. Therefore, while mature saskatoons will not likely be killed by WEA on the roots, the yield is negatively impacted. This can also be interpreted as indicating that WEA is a stress factor for mature saskatoon bushes.”

If you are thinking of propagating your own rootstocks please be aware that Ottawa #3 (better known as O3) is a public domain while V3 is a proprietary material.

Besides overcoming incompatibility and delayed incompatibility, interstem is useful for other purposes. M9 is the most widely used dwarfing apple rootstock in the world. It is very precocious but unfortunately has very poor root systems that cannot provide sufficient anchorage. (They must be supported for life either with individual stakes or wires.) So, someone came up with the idea of double working - using non-dwarfing rootstocks like M106 to provide good anchorage, grafting M9 onto it and then grafting the desired cultivar onto the M9. In this way well anchored dwarfing precocious apple trees are produced. (Who says you cannot have your cake and eat it too?) Unfortunately they soon ran into problems because the results were inconsistent and most plantings did not produced the desirable dwarfing effects. That resulted in heated debates on the wisdom of using double working for this purpose. It was later found that the length of the interstem played a critical role in the dwarfing effect. There must be a minimum of 8 inches for interstock for the dwarfing effect to kick in. (With today’s practice of ultra-high density planting commercial growers prefer to stake their trees instead of double working.)

Is interstem of any use to us on the harsh prairie? Most growers in Saskatchewan and a handful in Alberta use O3 or V3 as rootstocks. However O3 is not suitable in all areas. I find its stem is hardy but the roots are not; the roots must have consistent snow cover throughout winter. V3 was tested at CDCN for five years. Results were very encouraging but there is insufficient data to say with any confidence as far as its hardiness is concerned*. Gardeners in metropolitan Edmonton will have no problem with O3 or V3. However double working still merits consideration since we are in very windy country and strong gusts are frequent. In my opinion double working is definitely worth looking into for those living in Edmonton who want well anchored precocious dwarfing apple trees. Gardeners living outside the city or in rural areas may have no choice or will get better chances with double worked trees if precocious dwarfing apple/crabapple trees are desirable.

* O3 was among one of the rootstocks used as control. They failed before the test ended. Data from five years is insufficient for such long term cultural trial.

Enthusiasts of Bonsai, Penjing or container growing may find interstem useful. Malus spp. grown in containers are prime candidates for winterkill. More often than not the tops come through winter without injury but it is the roots that are completely killed. Using open pollinated seedlings as rootstocks I experienced much anguish over the years. I found most are killed in test winters but some are capable of tolerating the extremely cold even when the containers are not buried for added protection. My most hardy is an open pollination Viking crab. It was seeded in a container and after 21 years it is still very healthy without added winter protection. McIntosh grafted on it in 1997 is still productive while those grafted onto O3 and others died in one, at most three winters. In each and every case the buds began to move but dried up soon because the roots were dead. (In some cases the rootstocks were dead to the soil line and others were dead to the union.) Unfortunately this very hardy rootstock is neither dwarfing nor precocious.

Another potential commercial application is for disease control although I do not see any application for us. Rubber tree, Heavea brazillensis, is native to the Amazon Basin in Brazil. However Brazil lost its status as a major producer of rubber after Henry Wickham successfully smuggled some seeds out of the Orinoco Basin. Trees in Brazil are susceptible to a deadly disease known as the South American Leaf Blight (SALB), Microcyclus ulei. (Malaysia together with Indonesia, where SALB is absent, produce over 80% of the world’s natural rubber.) The useful or productive part of the rubber tree is the trunk. Since rubber cannot be propagated with stem cuttings, many Malaysian growers graft selected clones onto PBIG rootstocks. Unfortunately the crown of modern high yielding clones like the RIM 600 Series are very susceptible to this deadly disease. RRIM (Rubber Research Institute of Malaysia&) found a SALB resistant selection but it is totally useless because it is an extremely poor latex producer. Hence they embarked on the biggest double working trial in the world by testing the feasibility of having compound trees with 4 inches of PBIG, 8 to 10 feet of RRIM 604 and the rest of the top is the SALB resistant selection^. (The reason for the long interstem is because in harvesting only the bottom 8 feet of the trunk is tapped for the latex.)

& RRIM is the largest research institution in the world devoted to a single crop.

^ I do not know the results or the status of this trial because I left the country a few years after the trial was initiated.

Many of us are adding new cultivars to branches of existing trees. If the trees are on their own roots we are stem building. Agriculture Canada used to recommend using Malus baccata ‘Nertchinsk’ for stem building to impart winter hardiness. Most of us plant grafted trees and are merely adding more cultivars onto existing branches. Hence in a way we are using our grafted trees as the interstems. A word of caution is warrantied; multiple cultivars trees must be pruned carefully to avoid excessive growth and vigor of one cultivar to the detriment of another because some cultivars are more vigorous or compatible than others with the interstem.

This and That

Thank you, Dr. Ken Fry for responding to the last issue. Since almost all of us have saskatoon in our yard this information is of tremendous value.

Dr. Fry wrote. “As for WEA and its impact on saskatoons, they are most damaging to the establishment of saskatoon seedlings but in some research trials I did at CDC-North, I treated saskatoons with orthene to kill the aphids on the roots of saskatoons and left other saskatoons untreated and then recorded the yield over a period of 5 years. In the treated saskatoons, by year 3 the yield was significantly higher than the untreated. Therefore, while mature saskatoons will not likely be killed by WEA on the roots, the yield is negatively impacted. This can also be interpreted as indicating that WEA is a stress factor for mature saskatoon bushes.”

If you are thinking of propagating your own rootstocks please be aware that Ottawa #3 (better known as O3) is a public domain while V3 is a proprietary material.

DBG Fruit Growers’ Bulletin 3-17 added Sept. 4, 2017

Budding and Grafting Tidbits By Thean Pheh added Sept. 4, 2017

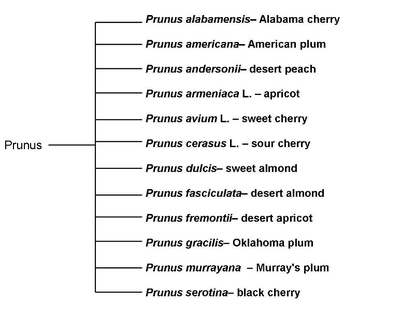

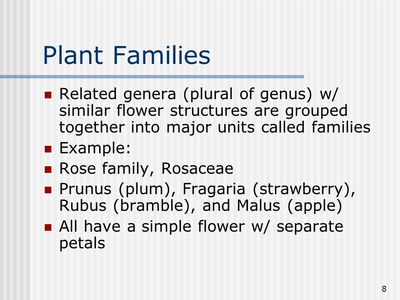

There is a universal system of classifying plants and animals. Normally only the bottom three, Genus, Species and cultivar, are mentioned. There is also a system of writing whereby the Genus and Species are written in italic and the cultivar is normal within a single quotation. For example the crabapple Columbia is written as Malus baccata ‘Columbia’. (Notice the first letter of the Genus is in uppercase while that of the Species is in the lower case.) It is a member of the Rose Family but the Family is not noted as it is assumed the reader either already knows what it is or where to find it.

Normally grafting is done between the cultivars (aka inter-cultivar grafting), for example grafting Malus baccata ‘Columbia’ onto Malus baccata ‘Renetka’. This presents the least problem. Inter-species grafts like Malus domestica ‘Goodland’ onto Malus baccata ‘Renetka’ are also very successful. Most of us are doing this. (My Heyer 12 grafted onto an open pollinated crab is over 60 years old and still very healthy and productive.) Inter-genera grafts tend to experience delayed incompatibility. Nonetheless they are widely used by commercial pear growers around the world where pears, Pyrus communis, are grafted onto quince, Cydonia oblongata. There is no record of any successful grafting outside the Family.

Most of us are growing fruits in the Rose Family like apples, pears, saskatoons, cherries, plums etc. Now, don’t jump too far ahead, yet. The Rose Family is very big and complicated with several subdivisions. Apples, pears and saskatoon belong to Maleae or pome tribe or subfamily while cherries, plums belong to the Prunoideae or stone fruit tribe. Members of the two tribes/subfamilies are not compatible: sorry you cannot graft apples onto plums.

Inter-genera grafting is widely practiced but is rarely publicized. Forced by very limited suitable land available for agriculture Korean, Japanese and Chinese farmers had been planting the same crop yearly, some for over a thousand years. That led to disease buildup in the soil. The only biological method to overcome the problem was to graft onto disease resistant rootstock. They have been grafting melons, Cucumis and watermelons, Citrullus onto various Cucurbita squashes before WW II. In Canada inter-genera grafting is not new either. It was tested by Agriculture Canada on apples, pears and other fruits after the war. As late as the early 1990s, grafting saskatoon (Amelanchier) onto cotoneaster (Cotoneaster) was the only mean of propagation for farmers in the Prairie Provinces.

Gabe Botar has experimented with inter-genera grafting for many years. Other members like Wayne Fuhr, Evelyn Mellot and Bernie Nikolai have also tested inter-genera graft for some time. Using cotoneaster as rootstock is not new in Canada. It was abandoned for valid reasons or as other better and cheaper methods of propagation become available. Nevertheless, the possibility of copying the Russians in Siberia of using cotoneaster as a rootstock for pears is worth revisiting. As with most inter-genera grafts there is delayed incompatibility. Luckily and thankfully the Russians have broken the ground for us. Let us take a short moment to understand the ins and outs of this phenomenon.

Most people think roots absorb water and nutrients from the soil. In reality only the very tiny, temporary and fragile root hairs (tiny strands of single cell found radiating from the tips of new elongating roots) are capable of performing this task or forming any relationship with beneficial soil microbes like mycorrhizae. The raw ingredients (RI) namely water and nutrients plus some hormones then travel in the xylems, found in the roots and stem, to the leaves. (The xylems are just a series of microscopic tubes found in new wood of woody plants and stem of herbaceous plants.) Through photosynthesis the leaves combine the RI with carbon (in atmospheric carbon dioxide) to produce manufactured products (MP) such as sugars, carbohydrates, proteins and other phyto-chemicals to feed the rest of the plants. These MPs travel through another series of microscopic tubes called the phloem found in the stems of all plants and easily visible as the living barks of woody trees. The roots, trunks and stems (aside from the root hairs, buds and leaves) are merely there for anchorage and to serve as conduits for transporting the RIs and MPs, and storages for excess MPs.

Thus there is a well defined system of ‘you feed me, I feed you’ or ‘you scratch my back I’ll scratch yours’. However when a plant is grafted this free flow is impeded, even in the most compatible graft. Budding or grafting involves two individual plants with different genes, abilities and habits. (Refer to earlier bulletins in 2014 and 2016.) Although each still maintains its own genetics there are sufficient interactions between the two to alter each other’s physical expressions. The impediment is at the union where connectivity is restricted or interrupted. In some cases it involves the xylem while in others it’s the phloem. When the impediment is not severe there is ‘give and take’ and the grafted plant is healthy, productive and long lived. Severe impediment results in delayed incompatibility. Delayed incompatibility is expressed differently in different grafts. Some grow well while others are unthrifty. Nevertheless, in either case the plants are short lived.